October is Family History month. In recognition of this popular pastime and the many valuable genealogy resources at the Municipal Archives, For the Record explores the origins and intellectual content of the Marriage Contract collection. There are 8,616 items in the series; the bulk of the material pre-dates 1908 when New York State instituted the marriage license requirement. Similar to license records, the contracts provide information essential for family historians. But they also reveal interesting data that illuminates the experience of new immigrants to the United States during the first decade of the twentieth century.

But first, why were the contracts created? The records help provide the answer. Most of the contracts consist of pre-printed forms with information filled-in as appropriate. There are two forms, both titled “Marriage Contract.” On one of the forms pre-printed text reads, “Now, therefore, in pursuance of Subdivision 4 of Section 11 of Article II of the Domestic Relations Law, as amended by Chapter 339 of the laws of 1901, the said [name of groom] and the said [name of bride] do from the date of this contract become Husband and Wife.”

The Municipal Library’s New York State publication collection includes a copy of The Laws of the State of New York, 1901. Turning to Chapter 339, §11 the text states “Marriage, so far as its validity in law is concerned continues to be a civil contract . . . that must be “solemnized.” The 1901 law amended an 1896 statute which specified that a marriage may be solemnized by 1) clergyman or minister of any religion, or the leader of the society for ethical culture in the City of New York; 2) mayor, recorder, alderman, police justice or police magistrate; or 3) a justice or judge of a court of record, etc.

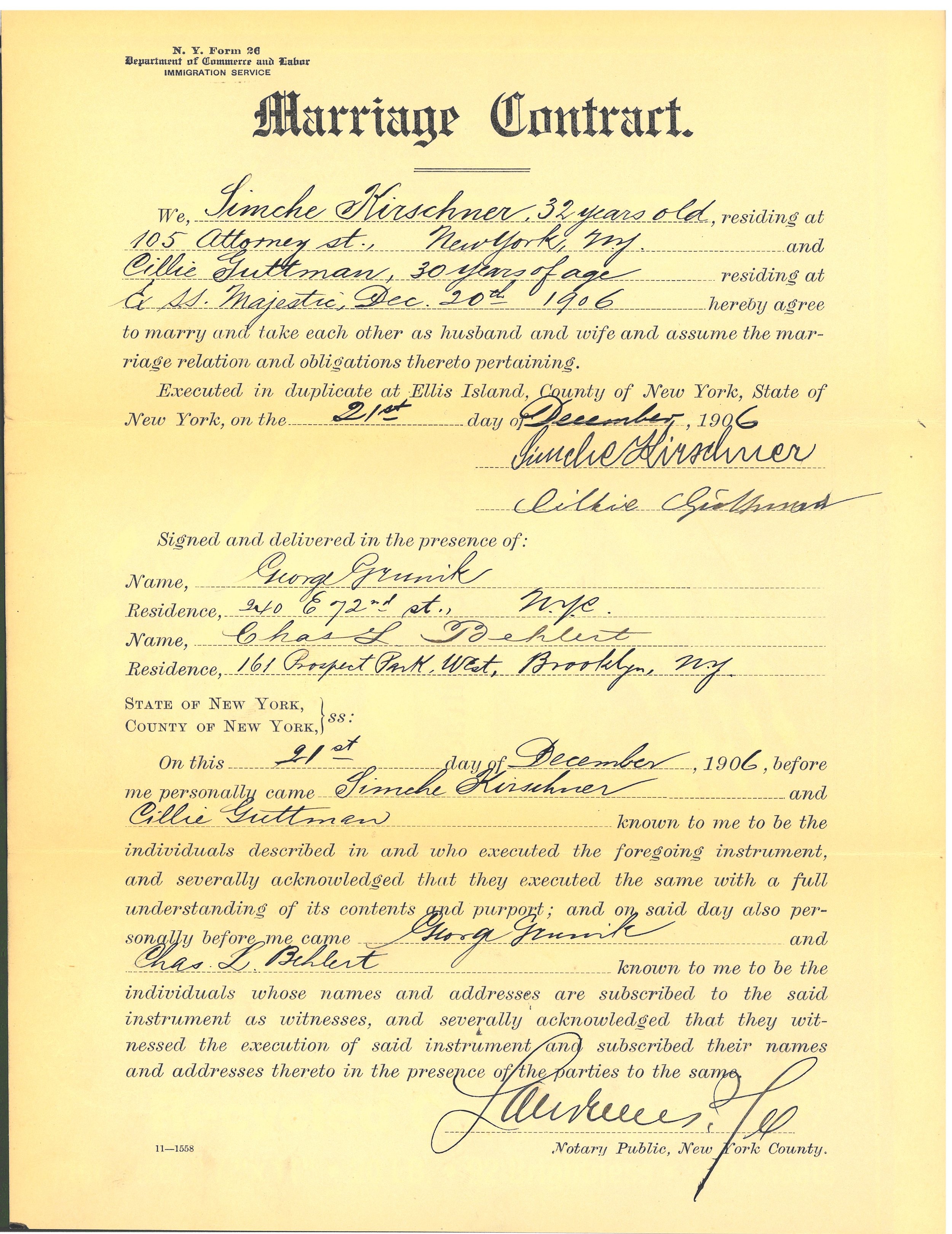

Marriage contract no. 8501. NYC Municipal Archives.

The 1901 amendment added a fourth method to validate a marriage: “A written contract of marriage signed by both parties, and at least two witnesses.” The amendment added “Such contract shall be filed within six months after its execution in the office of the clerk of the town or city in which the marriage was solemnized.” The Governor approved the amended law on April 12, 1901, and it became effective on January 1, 1902. Shortly thereafter, the New York City Clerk began receiving marriage contracts.

The contract series is a valuable resource for family historians. All of the contracts include basic data, e.g. names and dates. In some instances, additional information is provided, such as birthplaces and parents’ names.

Upon closer examination, the records also provide some fascinating insights into immigration. One notable feature of the series is that many of the couples have family names that point to origins in Southern and Eastern Europe. Given patterns of immigration at that time, the likelihood is that many were recent arrivals to the U.S. Further inspection shows that many were very new arrivals, i.e. marrying at Ellis Island on the day of arrival. As noted above, most of the contracts are pre-printed forms. One of the two forms that comprise most of the series was supplied by the “U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor, Immigration Service,” according to a stamp on the forms.

Examining marriage contracts that used the federal form reveals an interesting phenomenon. The grooms are almost always listed as residing in the U.S., mainly New York City. But the “residence” of the bride is frequently recorded as Ellis Island. For example, contract no. 2453: “We, Harry Askin, aged 25, residing at 357 E. 10th Street, N.Y.C. and Lei Stein, aged 18, arriving Ellis Island, S. S. Statendam on January 4, 1905, hereby agree to marry etc.”

Marriage contract no. 5709. NYC Municipal Archives.

Over the years, patrons visiting the archives have sometimes been in search of documentation to support a family legend that their ancestors married on Ellis Island. City archivists replied that there were not records; Ellis Island was not considered part of New York City for vital record purposes, and reporting of birth, death and marriage events to the City’s Health Department was not consistent. Now, with the newly indexed marriage contract series, maybe the family stories are true – and there are records to prove it!

A second observation about contracts using the Immigration Service form is that there are “witnesses” who signed multiple contracts. For example, during the last two weeks of August 1904, Helen A. Taylor, of 108 W. 84th Street, witnessed eleven marriages. All eleven brides “resided” on Ellis Island, having arrived on steamships within a day or two of the contract-signing. Although two grooms also listed Ellis Island as place of residence, all the rest resided locally. Similarly, Elizabeth A. Fitzgerald, of 404 E. 6th Street, witnessed five marriage contracts during December 1904. The newly-arrived brides all married U.S. resident grooms, often on the day the boat docked: “We, George W. Whitehead, 26 years, residing at 165 W. 21st Street, N.Y.C. and Edith Swain, 23 years, arrived at Ellis Island, S.S. Lucania, December 12, 1904, hereby agree to marry etc.,” signed December 12, 1904. (Marriage contract no. 2381.)

Marriage contract no 8497. NYC Municipal Archives.

This leads to further questions. Were the “witnesses” representatives of an altruistic organization such as the Immigrant Aid Society, or were they operating some kind of business enterprise? Did having the marriage contract ease entry to the U.S. through Ellis Island?

One possible answer comes from historical information supplied by the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services division of the Department of Homeland Security. According to their website, “During its first decade [after 1892], the Immigration Service formalized basic immigration procedures and made its first attempts to enforce a national immigration policy. The Immigration Service began collecting arrival manifests (also frequently called passenger lists or immigration arrival records) from each incoming ship, a former duty of the U.S. Customs Service since 1820. Inspectors then questioned arrivals about their admissibility and noted their admission or rejection on the manifest records. Beginning in 1893, Inspectors also served on Boards of Special Inquiry that closely reviewed each exclusion case. Inspectors often initially excluded noncitizens who were likely to become public charges because they lacked funds or had no friends or relatives nearby.”

Given this information, it seems apparent that having one of the two parties already residing in the U.S. probably assured quick passage through Ellis Island and a new life in America.

Once again, basic bureaucratic processes and the resulting documentation available in Municipal Archives collections help tell a larger story. And future digitization of the series will greatly expand this utility. In the meantime, the index to the contracts can be accessed by clicking on the ‘External Documents’ link in the Collection Guide description of the collection. Patrons can visit the Archives to view the contracts, or order copies using the online order form for historical marriage records.