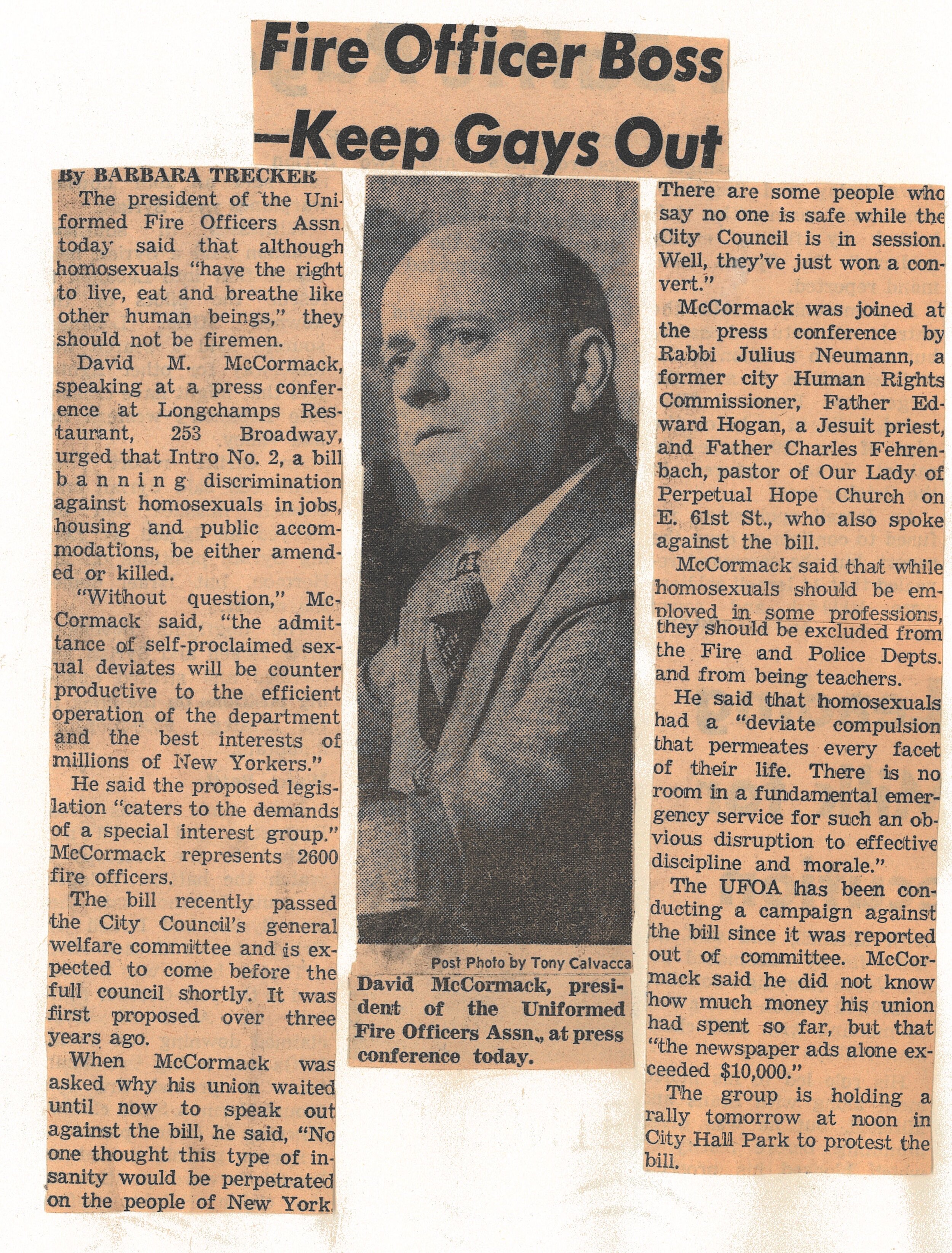

Recently the question of whether the City’s seal has outlived its useful life circulated in the media. The seal is omnipresent on letterhead and other documents issued by City government agencies and officials. While news stories date the current seal to a local law enacted in 1915, the imagery dates back much further. The Municipal Library’s Vertical Files (so called because they consist of file folders of media releases, news clippings and other material held in vertical file cabinets, not shelves) yielded a surprising quantity of material on the subject.

Camera art for the City Seal, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

An interesting history of the City’s seal was published in 1915 in the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society’s twentieth annual report. Titled “SEAL AND FLAG OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK” it traces elements of the seal to the City of Amsterdam in 1342 at which time William Count of Henegouwen and Holland “made a present to the Amsterdammers of three crosses on the field of the City’s arms.” Not just any crosses but “saltire” crosses which means a diagonal cross—shaped like an X, not a t, and sometimes called a St. Andrew’s Cross.

City seals and flags are outgrowths from the coats of arms and banners that initially came into use around 1100 when helmeted knights fought in battle. Distinctive color and design were required to identify who was behind a given helmet. An entire craft, heraldry, evolved. This “practice of devising, granting, displaying, describing and recording coats of arms and heraldic badges is complicated.” There are many rules around the shapes, designs, colors, patterns, and division of the shield into halves, thirds, quarters, etc. There is a separate set of directions for identifying where an item should be drawn or placed, consisting of numbered locations within the shield and, most important for our purposes, four cardinal points: chief for the top, base for the bottom, dexter for the left and sinister for the right (in Latin, dexter means right, and sinister left, but the positions refer to the shield bearer’s perspective). The design of New York City’s official seal incorporates all of these practices.

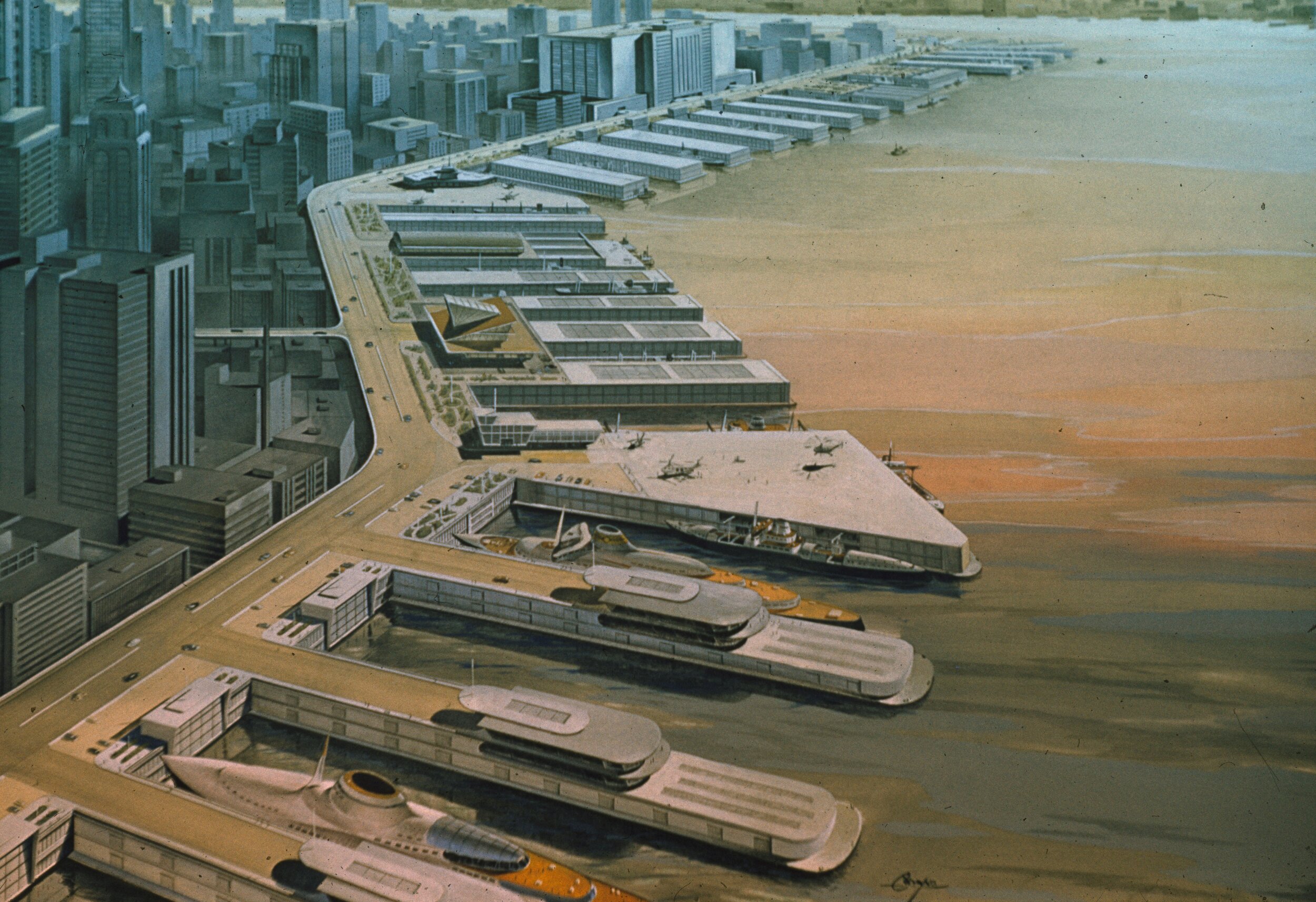

Evolution of the City Seal, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

One consistent feature on the New York City seal is the image of a beaver. The fur trade formed the basis of commerce for New Netherlands, including New Amsterdam and the beaver was the foremost symbol. Interestingly a beaver both had value as a commodity and as currency itself. In the Scenic Society’s report the author notes, “The intelligence and industry of these little animals, their ingenuity as house-builders and their amphibious character make them eloquent symbols also for the City of New York. So far as we know, the use of the beaver in the arms of New Netherland, New Amsterdam and New York City is unique in heraldry.”

Documentation on the ornamental cast-iron seals that decorated the old West Side Highway shows the evolution of the City’s seal. The Seal of the Province of New Netherland, adopted in 1623, is made up of two shields—the smaller contains an image of a beaver and the larger, which surrounds the smaller, consists of a string of wampum. It is topped by a crown and the outer border is ringed with the Dutch words for “Seal of the New Belgium.” (Holland and Belgium were united at that time.)

In 1653, New Amsterdam developed a municipal government, the Burgomasters and Schepens, which petitioned the West India Company for its own seal, which was received in 1654. Once again, there were two shields. Arranged one atop the other with a beaver between them, the larger shield contained three saltire crosses. There was drapery above and a label with the words “Seal of Amsterdam in New Belgium” at the bottom.

Tracing of the seal of New Amsterdam, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

Ten years later, the Dutch surrendered New Amsterdam to the English and the City was renamed New York, after the Duke of York. The provincial seal was centered around the coat of arms of the Stuarts and was encircled with the Latin words meaning “Evil to Him who evil thinks.” There is a crown atop the shield and all is encircled by a laurel wreath. This is the only seal without the otherwise ubiquitous beaver. In 1686, the rights of the City were affirmed by Governor Dongan in the Dongan Charter which also provided for a City seal. In the center is a shield on which the sails of a windmill are arranged in a saltire cross. There are two beavers and two flour barrels alternating between the crosspieces of the windmill. On either side of the shield are human figures—on the dexter side a sailor holding a device for testing the depth of water; on the sinister, a Native American image.

After the British evacuated the City in 1783, the new government updated the 1686 City seal to remove the Imperial crown. Atop the shield they placed an image of an eagle standing on a hemisphere. It’s dated 1686 to commemorate the Dongan Charter and the words “Seal of the City of New York” are inscribed in Latin. Most of these design elements are present in the City’s seal (and flags) today.

Seal of the Office of the Mayor, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

Sometimes the use of the City seal was contentious. Common Council minutes from 1735 address an apparent wanton use of the city seal without proper authorization and there was some concern that the Mayor was not providing the Council with use of the seal. The Council passed an ordinance that “lodges and deposits the common seal in the hands and custody of the Common Clerk” of the city—today the city clerk—and further banned alternative city seals. The ordinance restricted the use of the seal to actions taken by the Common Council or the Mayor’s Court.

A review of the archival records in the Office of the Mayor collection starting with the so-called “early mayors” shows that correspondence was not bedecked with official letterhead. In many letters the tops of the pages were blank. In other instances, the name of the agency writing the letter was hand written at the very top of the page, followed closely by the text of the letter, written in flowing cursive. That’s not to say that there wasn’t a City seal in use. But, its’ use was sparing, apparently deployed to certify some official documents, not run-of-the-mill correspondence. A case in point is an 1816 certificate issued by Mayor Jacob Radcliff certifying that a woman named Nancy, approximately 60 years of age, was a free woman and could travel. An embossed seal is embossed at bottom of the document. It bears all the elements of the seal in effect today.

In 1914, a group of former members of the Art Commission was appointed to provide an accurate rendering of the corporate seal of the City, and a design for a City flag. The various departments and boroughs had been using variations of the seal which created confusion about the provenance of official documents.

Based on the recommendation of this committee, in 1915 the Board of Alderman amended the City’s Code of Ordinances relating to the city seal, flags and decorations on city hall. The Aldermen re-established the 1686 seal as updated in 1784 and required it to be used for all documents, publications or stationery issued or used by the city, the boroughs and the departments. They made some minor style changes-the shape of the seal, the position of the eagle, etc. and also changed the date on the seal from 1686, the date of the Dongan Charter to 1664, the year the City was named New York.

It is in this legislation that a major error was made. Apparently the bill’s drafters were not versed in the heraldic arts. As a result, the cardinal directions of “dexter” and “sinister” were assigned as the names of the figures in each location. So the sailor holding a depth reading device was named “Dexter” for the left sided placement and the Native American figure placed on the right was named “Sinister.” How this happened is lost to history. One would think the high-profile former Art Commissioners would have sounded the alarm and corrected the error, which still exists.

In 1975, City Council President Paul O’Dwyer sought to change the founding date on the seal from the existing 1686 date marking the issuance of the Dongan Charter, to 1625 when the Dutch established New Amsterdam. The legislation also invalidated all former seals bearing the 1664 date.

As mentioned, not only is there a City seal, but each of the boroughs have separate seals or emblems dating to the colonial period. After consolidation of the Greater City in 1898, the boroughs continued to use these seals for various official purposes until 1938 when the Board of Estimate mandated that the seal of the City of New York would replace any previous seals that had been in use. Thereafter, the various seals were to be found on the borough flags and not on official documents. But the use of the seal continued to vex officials and in 1970, the Board of Estimate mandated that the seal of the City be placed on each letterhead and restricted the use of a gold seal to the Board of Estimate and the Vice Chair of the Council.

Seal of the Borough of Queens, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

The flag for the borough of Queens was announced in 1948 after a design competition. The three-paneled seal included a tulip commemorating the Dutch on the dexter side, a double Tudor rose documenting the English on the sinister side. The border consists of shells used as money “wampum.” At the very top of there is a crown signifying that the borough was named for a Queen, namely Queen Catherine Braganza wife of England’s King Charles the Second.

According to an excerpt in the files from a 1925 history, “the Boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens, Counties of Nassau and Suffolk Long Island, New York 1609-1924” Brooklyn’s seal was established by the West India Company in 1664. It consists of an image of the Roman goddess Vesta (equivalent to the Greek goddess Hestia) holding fasces—or bunch of rods and an axe bundled together. Apparently, this reflected the colony’s agricultural status. The motto surrounding the seal translates to “unity makes strength” which in 1664 was an update from the 1556 motto on the coat of arms of William the Silent, Prince of Orange. When the Village of Brooklyn officially incorporated in 1817, the seal was adopted by the common council.

Seal of Staten Island, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

The seal of the Borough of Richmond, aka Staten Island, has gone through several evolutions. The Dutch named the island after the “Staten General” of their legislature. One seal consists of two doves facing each other with the letter S (for Staten) between them and N YORK beneath their feet. Another early seal has a female figure gazing toward the water in which two ships sail, one purportedly Henry Hudson’s Half Moon. In 1970, the then- Borough President held a contest to develop a better emblem. The winner was an oval with waves surrounding an island with birds flying in the sky above and STATEN ISLAND written between the waves and the island. However, this design was not universally admired. The Staten Island Advance reported that current Borough President James Oddo redesigned the emblem in 2017 to incorporate elements of the woman gazing out on the Verrazzano Narrows as well as oystermen, a moon and stars.

The Bronx, by contrast, maintained its seal, adopting the coat of arms of Jonas Bronck who settled in the area in 1639. A sun rises from the sea and a globe topped by an eagle stands above it. The Latin motto under the shield translates to “do not give way to evil.” This same design was the basis for New York State’s post- revolutionary coat of arms.

Brooklyn Markets Seal, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.

Notwithstanding this requirement that the City seal be use on all official materials, some agencies developed their own seals. In 1940, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia announced the conclusion of a contest, with a $10.00 prize won by a high school student, to design a seal for the Department of Markets. The seal featured a scale, a bundle of wheat and two full cornucopias. More recently, the New York Police Department (NYPD) developed a seal described in the agency’s 1987 annual report. It’s a somewhat cluttered design with the names of the five boroughs creating an interior ring. The City seal is at the bottom and the upper portion includes the words Lex and Ordo (Law and Order). The scales of justice are balanced atop the fasce and what looks to be a rocket (but probably isn’t) explodes from the top.

NYC Housing Authority Seal, NYC Municipal Library vertical files.