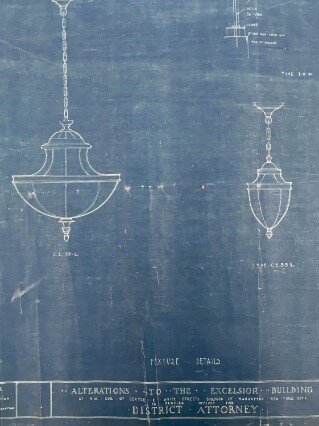

In 2018, with support from the New York State Library Conservation/Preservation Program, the Municipal Archives commenced a project to preserve and re-house approximately 100,000 architectural drawings and reproductions of buildings in lower Manhattan. Dating from 1866 through the 1970s, the plans comprise sections, elevations, floor plans, and details, as well as engineering and structural diagrams of buildings on 958 blocks in Manhattan from the Battery to 34th Street.

In the first year, project archivists cataloged and re-housed 11,882 plans for 977 buildings in the Tribeca and SoHo neighborhoods. With continued State Library support in 2021/22, the Archives preserved more than 18,000 plans for buildings in the Greenwich Village neighborhood.

For the Record has described project progress in several articles. Re-discovering the Old Pennsylvania Station highlighted original plans of the iconic building found in the collection. The Curious Case of the Lighting of the Williamsburg Bridge told the story of an experiment to power lighting for school buildings via a trash incinerator. Stables and Auction Marts: Building Plans with Horses detailed the significance of horses in 19th and early 20th century New York City. And Loew's Canal Street Theater featured the plans for the ornate Loew’s Theater on Canal Street.

26 Ridge Street, ca. 1940. 1940s Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Project archivists recently completed preservation and re-housing 11,350 plans for buildings in the Lower East Side and East Village with support from the State Library. This week, For the Record explores some of the interesting “finds” identified over the course of the project.

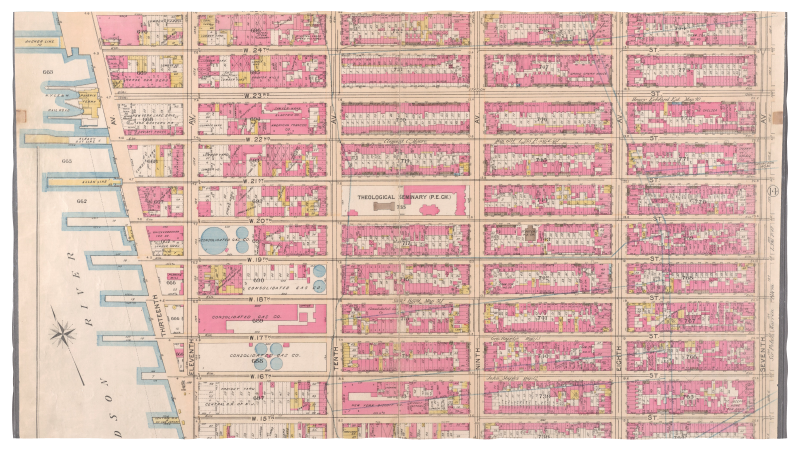

The Lower East Side and East Village have long been recognized as iconic neighborhoods to which millions of Americans can trace their roots. Their streetscapes have served as a backdrop for countless books, films and stories that chronicle the experience of generations of newcomers to the United States from around the world.

Plans preserved over the course of the project illustrate how these communities developed with examples of buildings of all types necessary for a thriving neighborhood. They include every style of residential building—from simple “tenements,” and more modern apartment buildings, to elegant single-family townhouses. Plans of retail establishments, banks, hotels, houses of worship, entertainment venues, bathhouses, factories, warehouses, boardinghouses, stables, garages—are also evident in abundance.

The Department of Buildings practice of requiring plans to be filed when issuing permits to build new buildings or to alter existing structures began in the late 1880s. This coincided with a period of intense immigration to the United States by Eastern European Jews who settled in the Lower East Side neighborhood; consequently, the collection is particularly rich in drawings reflecting those immigrant communities.

Religious institutions:

242 East 7th Street, cross section. Gross & Kleinberger, architects. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

242 East 7th Street, auditorium and balcony plans. Gross & Kleinberger, architects. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

242 East 7th Street, ca. 1940. 1940s Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 376 Lot 13

Congregation Beth Hamedrash Hagadol Anshe Ungarin (Great House of Study of the People of Hungary), designed by the firm of Gross & Kleinberger, this synagogue was built in 1908 at 242 East 7th Street, after the congregation had grown too large for its previous site. The second image shows seating in the auditorium and balcony.

172 Norfolk Street, plan for Russian and Turkish baths. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 355 Lot 4

Hand-drawn plan for another Hungarian synagogue located at 172 Norfolk Street; this alteration drawing from 1893 shows the building had Turkish and Russian baths, and dressing rooms on the lower floors.

26 Ridge Street. front elevation. Frederick Ebeling, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 341 Lot 38

A synagogue built in 1906, architect Frederick Ebeling, owned by Congregation Thebat Achim, and located at 26 Ridge Street; the front elevation plan shows an onion dome and a Star of David lunette.

Housing:

58-62 Hester Street, Longitudinal Section, Tenement House for Cortlandt Bishop, Esq. Ernest Flagg, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

58-62 Hester Street, Ground Floor, Tenemant House for Cortlandt Bishop, Esq. Ernest Flagg, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 298 Lot 15

1901 new build drawings for a “Model Tenement” by architect Ernest Flagg, located at 58-62 Hester Street; a longitudinal drawing featuring the building’s central staircase and a detail of the ground floor showing that although each apartment had its own “W.C,” showers and baths were shared spaces.

128 Broome Street, elevation. Michael Bernstein, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives. Some of the architectural flourishes were never built or were gone by the 1940s.

128 Broome Street, ca. 1940. 1940s Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 337, Lot 1

An apartment building at 128 Broome Street at the corner with Pitt Street; built in 1899 by architect Michael Bernstein, the façade has lovely detail work.

88 Ridge Street, Front Elevation, East Side of Ridge Street. Charles B. Meyers, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 343 Lot 43

80-82, 84-86, 88 Ridge Street; three adjacent 6-story brick tenements with stores on the ground floors and a shared tin roof and façade; built in 1892, architect Charles B. Meyers.

Architects Bernstein and Meyers are ubiquitous names in the Buildings Plans Collection, as they were prolific during the tenement housing boom.

Services and businesses:

New Closet Building at Grammar School No. 4, 203 Rivington Street, 1894. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 343 Lot 50

“New Closet Building” for Grammar School No. 4 from 1894, located at 203 Rivington Street. The drawing shows the old water closet facilities on the left and the much larger expansion facility, in the center a necessary alteration to keep up with the burgeoning population. Also notable are the separate “yards” for girls and boys.

101 Broome Street, coal bunker. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 336 Lot 43

More people meant a greater need for fuel. This is an interesting drawing of the interior of a concrete coal bunker featuring track and hopper; located at 101 Broome Street, built in 1907.

Bank of Max Kobre, elevation. Benjamin W. Levitan, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

41 Canal Street, ca. 1940. 1940s Tax Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 298 Lot 33

The Bank of Max Kobre, built in 1911, located at 41 Canal Street, was one of many privately owned “immigrant” banks that held deposits, made loans, and brokered steamship tickets to the community. The 1940 Tax Photograph shows it had become a funeral home, the Zion Memorial Chapel.

81-81 ½ Bowery, elevation. Samuel Sass, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

81-81 ½ Bowery, interior balcony and staircase. Samuel Sass, architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 303 Lot 9

Delicate 1909 alteration plans by architect Samuel Sass, showing signage and interior staircase for Shulman’s Clothing Store located at 81-81 ½ Bowery.

Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Williamsburg Bridge, view showing fish market, south entrance [Delancey] and Pitt Street. February 20, 1925. Photograph by Eugene de Salignac, Department of Bridges/Plant & Structures collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 337 Lot 9

1924 plan showing signage and zinc-lined wood tank for the Wenig Live Fish Company, located at 36 Pitt Street. A building that was photographed by Eugene de Salignac in 1925.

19 Ludlow Street, plan for a “Rockwell Matzoth Oven.” Max Muller Architect. Department of Buildings Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

Block 298 Lot 24

Colorful drawing for a “Rockwell Matzoth Oven” to be installed at 19 Ludlow Street in 1923; architect Max Muller’s name is seen on many plans for buildings on the Lower East Side.