Supplying a diverse and teeming city with fresh food has been a constant problem in New York. Farmers’ Markets, which have undergone a resurgence in recent years, are nothing new. In the early days of New Amsterdam, farmers and Native Americans simply brought their crops to town and set about hawking them, usually along the bank of the East River, known as the Strand. While references exist as early as 1648 to “market days” and an annual harvest “Free Market,” the process was unregulated and inefficient. Peter Stuyvesant, the Director General and the Council recognized this….

Auctions

This week we announced that several non-archival artifacts are available for purchase at an auction of selected Gifts to the City. Proceeds of the auction will benefit the Municipal Archives Reference and Research Fund (MARRF) which supports the work of the Municipal Archives and Library.

The Historical Vital Records of NYC

The Department of Records and Information Services launched Historical Vital Records of NYC this week. The site features more than nine million birth, death and marriage records, all freely available to browse, search and download. In less than 24 hours after the launch, people from across the globe—in Europe, United Kingdom, Australia, China, New Zealand, Argentina, Jamaica, Hong Kong, Fiji—to name just a few places, visited the site.

Family gathering in Queens, n.d. Borough President Queens Lantern Slide Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The Municipal Archives has always endeavored to use advances in technology to expand and facilitate access to its vast holdings. About ten years ago, DORIS leadership began promoting the benefits of digitizing the historical vital record collection. Their arguments were persuasive and funding was made available beginning in 2013.

“Friends of China” Parade in New York City’s Chinatown, December 1937. WPA Federal Writers’ Project Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

It was an incredibly layered undertaking that involved setting up the financial, physical and digital infrastructures to support the long-term project. In the first phase, Assistant Commissioner Kenneth Cobb procured contracts with eDocNY, a New York State Industries for the Disabled vendor, to digitize the records. Cobb led a team of technologists, database managers, digitization technicians, metadata creators, collections managers, preservation and conservation staff, to ensure the project’s success.

The vendor eDocNY produced excellent high-quality, full-color scans of the certificates—a vast improvement over the microfilmed images previously available. The digital image helped to improve accuracy in transcribing the records and provided another opportunity to engage with genealogy partners who, since 2003, had been indexing the collections from microfilmed and hard-copy sources.

The next phase was to make the new digital records available to a broader audience. In 2017, DORIS launched an application built by in-house developers that allowed reference staff to fulfill requests for vital-record copies more efficiently and accurately using the new color images. The vital-records application also provided onsite patrons with the ability to search and view the records. The “app” was a pivotal steppingstone.

Michael J Mahoney Park, n.d. Department of Parks and Recreation Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Once the digitization project with eDocNY successfully digitized more than eight million records, DORIS pivoted to digitizing the Marriage License series in-house. Over the past several years more than one-million records have been digitized, preserved, and made available. The project was interrupted during the pandemic and picked up again in August, 2021. This work is on-going.

Further, City archivist Patricia Glowinski has begun working on a comprehensive guide to the New York City vital records, documenting records created and/or maintained by the City of New York, and vital records created and/or maintained by municipalities that were once located within the boundaries of the present-day five Boroughs that were dissolved or annexed before 1898. The collection includes birth, marriage, and death registers, certificates, and indexes, and marriage licenses, 1760-1949 (with gaps).

On the steps of a school, n.d. Municipal Archives Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The agency’s application development team tested a variety of open-source approaches to making the vital records available in a timeframe that internet users expect. They built a robust, secure, easy-to-use platform, capable of handling a large volume of users simultaneously. As a result, on day one, more than 25,000 users accessed the site and downloaded 12,000 records.

With each step, access to the collections increases, and the Municipal Archives continues to build and sustain industry-standard plans to manage the physical and digital collections, and the associated descriptions that provide access points. It is to the credit and expertise of archivists, conservators, and reference and research professionals at the New York City Municipal Library and Archives, that these collections will survive for future generations, and continue to enrich the research experience of people and communities around the world.

Family in tenement kitchen, n.d. Municipal Archives Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

Stay tuned for more announcements!

Department of Buildings - Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, 1866-1977

The Western Union Telegraph Company Building, 60 Hudson Street, Perspective of Hudson & Thomas Streets, May 29, 1928. New Building application 278 of 1928. Architects: Voorhees, Gmelin & Walker. Department of Buildings - Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 144, Lot 33-56. NYC Municipal Archives.

For the researcher investigating the built environment of New York City, material contained within the Municipal Archives is a gold mine. Recent blogs have described three of these resources, the Assessed Valuation Real Estate Ledgers, the Manhattan Department of Buildings docket books, and the Manhattan building plan collection, part 1, and part 2.

This week’s subject is another series from the Department of Buildings Record Group (025)—the application permit folders, a.k.a. the block and lot folders. The series is a subset of the Department of Buildings Manhattan Building Plan Collection, 1866-1977 (REC 074).

Totaling approximately 1,230 cubic feet, the permit folders provide essential and detailed construction and alteration information for almost every building in lower Manhattan from the Battery to 34th Street. In addition, a wide range of historical subjects can be explored using these records including the effect of planning, zoning and technology on building design, the role of real estate development as a gauge of national economic trends, and the evolution of architectural practice, particularly during the period of professionalization in the latter part of the 19th century.

Established in 1862, the Department of Buildings (DOB) “had full power, in passing upon any question relative to the mode, manner of construction or materials to be used in the erection, alteration or repair of any building in the City of New York.” All DOB personnel were required to be architects, masons, or house carpenters. Then, beginning in 1866, New York City law required that an application, including plans, be submitted to the DOB for approval before a building could be constructed or altered.

The provenance of the collection in the Municipal Archives dates to the 1970s when the DOB began microfilming the application files and plans as a space-saving measure. They intended to dispose of the original materials after microfilming. The project began with records of buildings in lower Manhattan, proceeding northward to approximately 34th Street when it was discovered that the microfilm copies were illegible. The DOB abandoned the project and the original records were transferred to the Municipal Archives for permanent preservation and access.

NB Application 34 of 1890, page 1, for a “Nurse Building” to be appended to the Society of the New York Hospital at 6 West 16th Street. Architect: R. Maynicke for George B. Post. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 817, Lot 29. NYC Municipal Archives.

NB Application 34 of 1890, page 2, for a “Nurse Building” to be appended to the Society of the New York Hospital at 6 West 16th Street. Architect: R. Maynicke for George B. Post. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 817, Lot 29. NYC Municipal Archives.

Most applications are accompanied by a site plan showing the building’s location. Site plan for the “Nurse Building” at 6 West 16th Street. NB Application 34 of 1890. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 817, Lot 29. NYC Municipal Archives.

New Building (NB) Applications

In theory, there should be an NB application for every building constructed after 1866. Unfortunately, prior to the mid-1960s, DOB policy was to dispose of the files of buildings that were demolished. The result is that the Municipal Archives collection generally comprises only records of buildings extant as of the mid-to-late 1970s.

The NB application provides the most complete and detailed information about a structure. The form includes location (street address and block and lot numbers); the owner, architect and/or contractors; dimensions and description of the site; dimensions of the proposed building; estimated cost; the type of building (loft, dwelling factory, tenement, office, etc.); and details of its construction such as materials to be used for the foundation, upper walls, roof and interior. Every NB application was assigned a number, beginning with number one for the first application filed on or after January 1, up to as many as 3,000 or more by December 31, each year.

Specifications form, front NB application 222 of 1919, the Cunard Building, 25 Broadway. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 13, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

Specifications form, reverse, NB application 222 of 1919, the Cunard Building, 25 Broadway. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 13, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

As buildings incorporated new technologies such as elevators and steel-frame construction, the approval process became more rigorous, requiring more extensive information about the proposed structure. Permit folders for larger buildings often contain voluminous back-and-forth correspondence between the DOB examiners and the owners and architects. If any part of an NB application was disapproved the owner or architect was obliged to file an “Amendment” form stating what changes would be made to the application so that the building would comply with building codes.

Amendment to NB Application 44 of 1925, filed November 23, 1926 for the building at 35 Wall Street. Each point on the amendment explains how the architects were modifying their plans to meet DOB objections. (Note point no. 4. “The height of the Wall Street front has been altered to meet the requirements of the Building Zone Resolution—Article 3, Section 8. All setbacks have been clearly noted on elevations and setback plan.)” Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 26, Lot 1. NYC Municipal Archives.

Correspondence from the Commissioner of the Department of Public Works in the Office of the President of the Borough of Manhattan, to the Department of Buildings regarding NB application 222 of 1919 (the Cunard Building at 25 Broadway), and possible disruption to sewers and sidewalks, August 21, 1919. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 24, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

Correspondence from the Zoning Committee to the Department of Buildings regarding the height of the Cunard Building, 25 Broadway, NB application 222 of 1919. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 24, Lot 27. NYC Municipal Archives.

When the DOB approved a NB application, they issued a permit and construction could begin. Periodically during construction, inspections would be made by DOB personnel and their reports would also be included in the application file.

Other Applications

After a building was completed and the final inspection report submitted, any subsequent work on the building would require a separate Alteration (ALT) application. As building technology became more complex, the DOB began to require separate applications for elevator and dumbwaiter installations, plumbing and drainage work, certificates of occupancy and electric signs. The permit files also contain numerous Building Notice (BN) applications pertaining to relatively minor alterations. The DOB also mandated a “Demolition” application to raze buildings. The permit files generally do not include documents related to building violations.

DOB building permit folder, Block 551, Lot 21, 26 West 8th Street. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The DOB organized all applications and related correspondence into folders according to the block and lot where the building was situated. After 1898, each block in Manhattan was assigned a number, beginning with number 1 at the Battery, and each lot within the block was also assigned a number. The original block and lot filing scheme has been maintained by the Municipal Archives for the block and lot permit collection. An inventory of the permit folder collection is available in the new online Municipal Archives Collection Guides.

The Municipal Archives has also maintained the original permit folders, whenever possible. The folder lists the application paperwork contained within and serves as a table of contents. If paperwork related to an application listed on the folder is missing, it is possible to trace at least basic information about the action using the DOB docket books as described in a recent blog Manhattan Department of Buildings docket books.

American Exchange Irving Trust Company, to the DOB, December 28, 1928, regarding application to the Board of Standards and Appeals. NB application 419 of 1928. Irving Trust Company Building at One Wall Street. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 23, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

Application for Variation from the Requirements of the Building Zone Resolution filed by the American Exchange Irving Trust Company, for One Wall Street, NB application 419 of 1928. Department of Buildings —Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 23, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives. (N.B. The variance was approved.)

Building bulk calculation diagram submitted with Application for Variation from the Requirements of the Building Zone Resolution filed by the American Exchange Irving Trust Company, for One Wall Street, NB application 419 of 1928. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 23, Lot 7. NYC Municipal Archives.

The collection provides detailed data about specific buildings and enables the researcher to explore broader topics. For example, one theme of interest to architectural historians is the impact of New York’s 1916 zoning ordinance. The regulation had been imposed partly in response to construction of the massive Equitable Building on lower Broadway, but more generally to reduce the growing density of the built environment. It is usually argued that the law was responsible for the setback style of New York skyscrapers constructed throughout the 1920s. In an examination of the NB applications for several skyscraper buildings erected before the Depression, such as the Irving Trust tower at 1 Wall Street, it was found that very often the original NB application was disapproved, in part because the building plans violated some part of the 1916 zoning ordinance. In response, however, the architects did not revise their plans, but instead appealed to the City for a variance and invariably received permission to proceed with their original plans.

Application to convert a stable to a sculptors studio, ALT 531 of 1903, no. 26 West 8th Street / 5 McDougall Alley. Department of Buildings—Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 551, Lot 21. NYC Municipal Archives.

The permit folder collection also provides ample opportunity for researchers to study the long tradition of adaptive re-use of buildings in lower Manhattan. Although many of the buildings in these neighborhoods pre-date establishment of the DOB, the collection is rich with applications submitted for later alterations, as architects, homeowners, and developers converted older structures into “modern” dwellings by removing stoops and covering facades with light-colored stucco, mosaic tile, and shutters.

Correspondence from architect Cass Gilbert to DOB, September 22, 1905. NB application 1376 of 1905, 90 West Street Building. Manhattan Block and Lot Collection, Block 56, Lot 4. NYC Municipal Archives.

The permit folders, along with the associated building plans, contain documentation for the study of individual architects, as well as architecture as a profession. Scholars will find an abundance of unique materials that detail the professionalization of the field, especially during the latter half of the 19th century.

Together with the Assessed Valuation of Real Estate ledgers, the several Department of Buildings series—docket books, architectural plans, and the permit folders, provide an unparalleled opportunity for detailed research on the built environment. Few other cities in the nation possess a body of documents whose scope and completeness can compare with these New York City records.

The Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959

This blog will describe the Manhattan DOB docket book collection; future blogs will provide information about extant docket books for the other boroughs.

On June 9, 1977, Eugene J. Bockman, Director of the Municipal Reference and Research Center (and the first Commissioner of the Department of Records and Information Services), wrote to Department of Buildings (DOB) Commissioner Jeremiah T. Walsh alerting him to “. . . a potentially dangerous situation” regarding the DOB docket books dating from 1866 through 1915.

In the 1970s, the DOB was located on the 20th floor of the Municipal Building and the docket books were on open shelves in a public hallway outside their offices. Bockman explained that it had been brought to his attention that the docket books were being “borrowed” for periods of time and not always returned. Bockman offered to house the books in the Municipal Reference and Research Center, located on the 22nd floor of the Municipal Building. He noted that they would be under “constant supervision” by the librarians but still easily accessible to DOB staff and others requiring access.

“The docket books . . . are extremely valuable historical resources,” Bockman added.

Walsh granted Bockman’s request and the pre-1916 docket books were moved to the Library. Three years later, in March 1980, the Municipal Archives accessioned the docket books from the Library. Municipal Archives staff working on the grant-funded Manhattan Building Records project at that time made frequent use of the docket books. In April 1982, the Municipal Archives accessioned the docket books dating from 1916 through 1959 from the DOB. During the 1980s, the Archives solicited donations to re-bind several of the earliest volumes. The Archives microfilmed the entire docket book series in 1989.

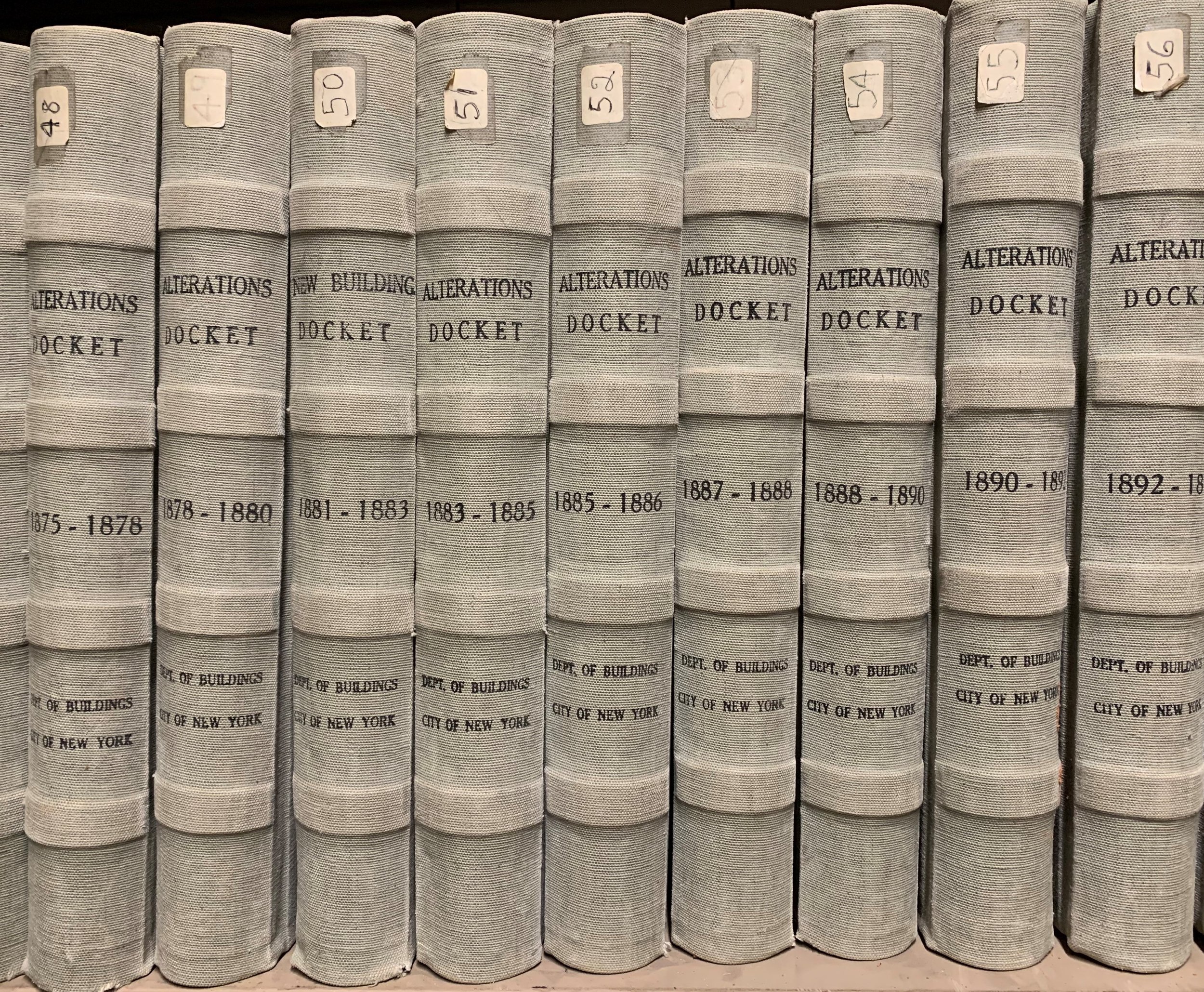

Manhattan Department of Buildings Alteration Docket Books. Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959. NYC Municipal Archives.

There are five series in the docket book collection:

New Building Application dockets, 1866-1916, (31 volumes)

New Building Docket Application Index dockets, 1866-1911, (29 volumes)

Alteration Application dockets, 1866-1910, (29 volumes)

Alteration Application Index dockets, 1866-1915, (37 volumes)

Application dockets, 1916-1959, (151 volumes).

On June 4, 1866, the DOB began requiring the filing of written applications, with plans, for the construction of new buildings or alterations to existing structures. They began recording summary information about each application in large, ledger-type books. Prior to 1916, they maintained separate ledgers for new building and alteration applications, and alphabetical indexes to each series.

Left and right pages of the New Building application docket book from 1880. No. 829 is the application to building no. 1 West 72nd Street, later known as the “Dakota” apartment building.

The building application was filed with the “French Flats” classification, a designation the DOB used after 1874 to denote a multi-family dwelling with more amenities designed to appeal to middle-class families. Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959. NYC Municipal Archives.

The New Building and Alteration Application ledgers are organized in column format on two facing pages in two sections; across the top of the page and then continuing across the lower portion. The pre-1916 ledgers record extensive information about each application.

Reading left to right, headings at the top of the left-hand page:

Plan no. /Date Submitted /Location /Street No. /Owner /Architect /Building /Ward No.

Reading left to right, headings at the top of the right-hand page:

Value /Size of Lot /Size of Building /Height in Stories /Foundation Specifications /Upper Walls Specifications /Materials of Front /Type of Roof /Material of Cornice.

Reading left to right, headings at the lower half of the left-hand page:

Plan No. /Iron Shutters /Configuration of Roof /Access to Roof /Type of Walls /Strength of Floors /Trap Doors /Fire Escapes /Type of Furnaces /Type of Building (1st Class Dwelling, 2nd Class Dwelling, etc.)

Reading left to right, headings at the lower half of the right-hand page:

Approved /Not Approved /Amended and Approved /Date Commenced /Date Completed /Name of Inspector /Remarks.

In April 1916, the Manhattan office of the DOB began recording docket book information on 10 ½” square typewritten forms bound into volumes.

The new typewritten form also coincided with an expansion in the number and types of applications recorded in the docket books. In addition to the New Building (NB) and Alteration (ALT) applications, the ledgers also included Demolition Permits (DP), Building Notices for minor work (BN), Electric Sign applications (ES), Dumbwaiter installations (DW), Sign Applications (SA), Computations (determination of safe floor loads), Elevators (sometimes accompanying alteration or new building applications), and Plumbing & Drainage Applications (P &D).

New Building (NB) Applications filed April 23, 1931. These entries include the first building applications for Rockefeller Center, including the RCA Building (NB 77 of 1931) and an early, unbuilt version of Radio City Music Hall (NB 78 of 1931). The entry is the only extant government record for this structure since the application itself was disposed when it was withdrawn. Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959. NYC Municipal Archives.

The typewritten format adopted by the DOB in 1916 improved legibility and permitted more narrative accounts, especially important for alteration applications. Alteration application 176 of 1931 pertaining to 35 Beekman Place is an example. It had been built as a private residence in 1866, and later altered to a tenement (i.e. multi-family dwelling) when the area became less desirable. As recorded in the 1931 application, the building would be altered back to a single- family residence in keeping with the revival of Beekman and Sutton Places as fashionable residential neighborhoods. Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959. NYC Municipal Archives.

New Building Application Index, 1880. Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959. NYC Municipal Archives.

There are several ways to find a docket book entry.

If the New Building application dates between 1866 and 1911, or the Alteration application dates between 1866 and 1915, the index volumes can be searched to identify the application number and relevant entry in the NB or ALT dockets. The indexes are based on location—i.e. street address of the building. In many instances, the location is rendered in distance from a street or avenue. For example an entry in the 1880 NB index for the letter “E” written as “83 S.S. 125’ W. 10th” translates to: 83rd Street, South Side, 125-feet west of 10th Avenue. It is also important to note that street names may have changed in the succeeding decades. For example, the Dakota Apartment building, is listed on the 1880 index under the letter “E” for Eighth Avenue; the name change to Central Park West did not take place until the 20th century.

Another avenue to identifying application numbers is the Department of Building’s website. Entering building address or block and lot numbers into the search box on their Building Information System (BIS) brings up a “Property Profile Overview.” At the bottom of that screen there is a “select from list” box where the application type, e.g. NB—New Building, can be chosen. After clicking “show actions” the relevant New Building application number will appear in the search results. Using the Dakota apartment building again as an example, entering the current address, 1 West 72nd Street results in NB 829-80* in the search result. (The asterisk indicates the date is 1880, not 1980.)

Another approach is using the searchable database created by the Office for Metropolitan History (OMH). Founded in 1975 by the late Christopher Gray, an architectural historian and journalist (he wrote the popular “Streetscapes” column in the Real Estate section of The New York Times from 1987 to 2014), the OMH website is another excellent resource for identifying New Building applications filed after 1900. The OMH data was entered from building application information published in the Real Estate Record and Builders Guide. Digitized copies of the Real Estate Record, 1868 through 1922, are available from Columbia University Libraries Digital Collections. Although the online Real Estate Record is not a particularly user-friendly tool, it is still a great resource for the pre-1900 information not available in the OMH database.

New Building Applications Filed March 30, 1922. Application no. 188 for a two-story fireproof garage. It was designed by architect Hector C. Hamilton. Manhattan Department of Buildings Docket Book Collection, 1866-1959. NYC Municipal Archives.

Tunnel Garage, 1940 Tax Photograph Collection. NYC Municipal Archives.

The OMH database is particularly useful for researching demolished buildings, or finding information that isn’t on the DOB website. In 2006, a building known as the “Tunnel Garage,” located on Broome Street, near the entrance to the Holland Tunnel, was demolished despite a vigorous campaign by preservationists. According to the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, the garage had been admired for its “bold graphic lettering, its green and orange terra cotta ornamental accents, its original casement windows, and its striking rounded corner.” It fell into disrepair during the 1980s and was replaced by a nine-story luxury condo. Perhaps tenants of the new building might want to know something about what previously stood on the site. If they did, the answer is readily available by entering address data into the OMH database: NB application: no. 188 of 1922.

The Municipal Archives’ related collection, the Manhattan DOB ‘block and lot folder’ series also serves as an option for identifying application numbers for buildings in lower Manhattan, below block 965. As described in previous blogs [add link], the “block and lot folder” portion of the DOB collection contains the original written applications. Most folders show the application contents listed by application number. But if the application is missing from the folder, the docket books can at least supply summary information.

In addition to providing information about specific buildings, the docket books serve to document the work of architects practicing in the city, and general research on the built environment. Mosette Broderick, Clinical Professor of Art History, New York University, spent many hours at the Archives in the early 1980s reviewing all the New Building and Alteration docket books from 1866 through 1910. “I learned how the city grew,” Professor Broderick remembered in a recent conversation. By tracking new building location information in the dockets she could see patterns of development. She also added that she discovered several smaller, less well-known projects by the renowned architect Stanford White in the dockets.

Eugene Bockman’s remark about the importance of the docket books was accurate and prescient. They have served generations of researchers and future digitization (they are on the priority list) will enhance their significance.

The Eastern District of Brooklyn

There is, in the Municipal Library, a charming tome titled The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps. Published on May 7, 1912, its author, Eugene L. Armbruster, was a preservationist long before that was a recognized field. An immigrant from Germany to the United States, he devoted years to documenting Long Island (which included Brooklyn and Queens) with photographs, pamphlets and other publications. Thousands of his photos are in collections at the New York Historical Society, the Brooklyn Public Library and the Queens Public Library.

Ferry Landing, Grand Street, Williamsburgh, 1835. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

Armbruster frequently answered questions posed by readers of The Brooklyn Eagle in a section of the paper titled “Questions Answered by the Eagle.” This idiosyncratic feature contained a hodge-podge of information in response to inquiries such as, “Is there a Shenandoah in New York?” submitted by BLANK…. Yes, in Dutchess County. “What is meant by the seven ages of man and who was the author?” posed by Mrs. D.H. … It’s from As You Like It by William Shakespeare spoken by the Duke in Act 2 (although the better-known portion of that speech is “all the world’s a stage and all the men and women merely players”). Labeled “the local expert on Brooklyn history,” Armbruster fielded questions related to events and places in Brooklyn, such as the original location of Litchfield Mansion. Right where it remains at 5th and 9th Ave., also known as Prospect Park West.

The book itself is tiny, about the size of a box of notecards but it contains a host of information in its series of brief sketches, appendices and hand-drawn illustrations and maps. The titles themselves are beguiling: a settlement named Cripplebush, one appendix titled, “The Solid Men of Williamsburg, 1847,” and the illustration listed as Literary Emporium. Is there such flora as a cripplebush and if so, what does it look like? Were the Williamsburg men particularly chunky? Was the emporium a bookstore or early library? The answers lie ahead.

Junction of Broadway, Flushing and Graham Avenues. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

Written shortly after the consolidation of the Greater City in 1898, the author intended to provide an overview of the Eastern District of Brooklyn to assist future historians. “If a history of the City of New York will ever be written, its compiler will look around for historical matter relating to the old towns, now forming parts of the metropolis, and this book was written that the Eastern District of Brooklyn may be represented then. But, what exactly is this Eastern District? Armbruster explained that during an earlier Kings County consolidation, the towns of Williamsburg, Bushwick and North Brooklyn were combined into the Eastern District. There also was a Western District that “included the remainder of the enlarged city” which was the portion of Kings County that comprised the City of Brooklyn. But that’s not all. There was a “sparsely settled” 9th ward between the two districts and a 26th ward that “was never a part of the Western District, but a town by itself until annexed in 1886 by the late City of Brooklyn.” Clear as mud!

Suffice it to say that the book is about a series of settlements that became villages, towns and cities between 1638 and 1910. These include what are now Ridgewood and Long Island City (now in Queens), Bushwick, Greenpoint, Williamsburg and East New York. The boundaries of the settlements shifted based on grants issued by the West India Company, colonial governments and eventually through Acts of the State Legislature.

Armbruster appears not to have accessed primary source documents and instead relied on several historical analyses. Mostly but not entirely written in the mid-to late 19th century, the authors include Henry R. Stiles, a physician and historian who penned the multi-volumed The Civil, political, professional and ecclesiastical history, and commercial and industrial record of the County of Kings and the City of Brooklyn, N.Y. from 1683 to 1884, and E.B. O’Callaghan who is best known for his (flawed) translation of original Dutch government and West India Company records.

Burr & Waterman’s Block Factory, Kent Avenue and South 8th Streets, 1852. This factory made “patent blocks” bricks of patented designs that were stamped with a company logo. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

One issue with the writing is the description of Native Americans in derogatory terms that are based on a versioning of history in which the European settlers were beneficent and the original residents of the land somehow miscreants. For example: “Over the morass led narrow trails, known to the redskins and the wild beasts, but treacherous to strangers.” Even when reporting on the murder of Native American families ordered by the Director General Willem Kieft, Armbruster maintains this form.

“In an evil hour Kieft ordered some of his men to the tobacco-pipe-land and another band to the Indian village, Rechtauk, situated two miles north of the fort on the East River (the present Corlear’s Hook), while both places were occupied by some fugitive Wesquaesgeek Indians, and had them cruelly slaughtered, men women and children, under cover of night. When the savages found out that the white men had committed the outrage, which they had first believed to be the work of an hostile Indian tribe about a dozen of the neighboring tribes of River Indians rose up against them and attacked the several plantations.” Who, one asks, should be more appropriately termed savage?

He devotes a brief chapter to the town records of Bushwick (Boswijck from “bos,” meaning a collection of small things packed close together, and from “wijk”—retreat, refuge, guard, defend from danger). This topic interests researchers and staff at the Municipal Archives. “When Bushwick became part of the City of Brooklyn the records were, in accordance with an article of the charter of the enlarged city, deposited in the City Hall. They were sent there in a movable bookcase, which was coveted by some municipal officer, who turned its contents upon the floor, whence the janitor transferred them to the papermill.”

Not all went to the papermill. The Municipal Archives collections includes the Old Town records which includes 60 volumes from the towns and villages in Kings County during the Dutch and English colonial periods.

In one beautifully written paragraph, Armbruster describes the rise and fall of the four mile stretch of Nassau River, known at the time of publication and today as Newtown Creek. “In the background were the hills covered with trees… At that time the creek, with the several gristmills, and the farms bordering thereon, differed in no way from the rural scenes, which are often seen as typical of Holland, except for the hills in the background. But since then the mills have vanished and factories and coal yards have taken their places and commercialism in general, with no eye for landscape beauty has taken hold of the territory. The water of the creek has been polluted to such a degree that the name of Newtown Creek has come into ill-repute, and it is well that the waterway, when cleansed and improved, will be known by the euphonious name of Nassau River.

Williamsburgh Gas Works Office, 93 South 7th Street, 1852. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

Phoenix Iron Works, 230 Grand Street, 1852. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

On the list of federal Superfund sites for the past decade, perhaps when the Environmental Protection Agency does undertake cleaning up the toxic waste, Newtown Creek will be again named Nassau River.

Map of the area north of Newtown Creek. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.

The appendices include three sections providing census information. Number 9 from the Census of Kings County circa 1698, lists the names of freeholders, and enumerates their family members, apprentices and enslaved people within Kings County “on Nassauw Island.” There were 51 freeholders, including four women. Eleven were of French ancestry; one was English and the remaining 39 were Dutch. In addition to the freeholders there were 49 women (presumed wives) 141 children, 8 apprentices and 52 enslaved people.

Appendix Number 12 provides the number of all inhabitants in the Township of Bushwyck, male and female; black and white, in 1738. The total of 325 “Ziele” (souls) listed 41 freeholders, including six women. There were 119 white males; 130 white females, 42 black males and 36 black females.

Appendix 13 offers a list of householders in one district of Bushwick. The 22 householders enslaved 20 men and 21 women.

A list of all the Inhabitants of the Township of Bushwick-Both White and Black-Males and Females, in 1738. An illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. Appendix XII. NYC Municipal Library.

This data shows that the colonial households and economy of Bushwick grew increasingly reliant on slave labor. The 1698 census shows that 21 households included enslaved people and five of the 30 remaining households listed apprentices. By 1738, 25 of the 41 households in the census listed black residents, who we presume were enslaved.

And now, to our initial questions.

Cripplebush was an area of land that stretched from Wallabout Bay to Newtown Creek and so named because of the thick scrub oak that flourished there, which the Dutch called kreupelbosch meaning thicket. The actual hamlet, which received a patent in 1654 was located around what today is South Williamsburg, just north of the Marcy Houses operated by NYCHA.

In 1847, a publication was issued listing the men of Williamsburgh and City of Brooklyn who owned $10,000 or more in personal property or real estate. The Solid Men of Williamsburgh refers to the 44 men living in that town who met this economic threshold.

As for the Literary Emporium—who knows. The illustration does not offer a clue as to its purpose.

Literary Emporium, corner of 5th and Grand Streets, 1852. Illustration from The Eastern District of Brooklyn with Illustrations and Maps, 1912. NYC Municipal Library.