What do the musical comedy star Ethel Merman, a troupe of young people dressed in “native” American garb, one live turkey, and a black and white cat named Felix have in common? They all played a role in the festivities celebrating arrival of the replica ship, Mayflower II, in New York City on July 2, 1957.

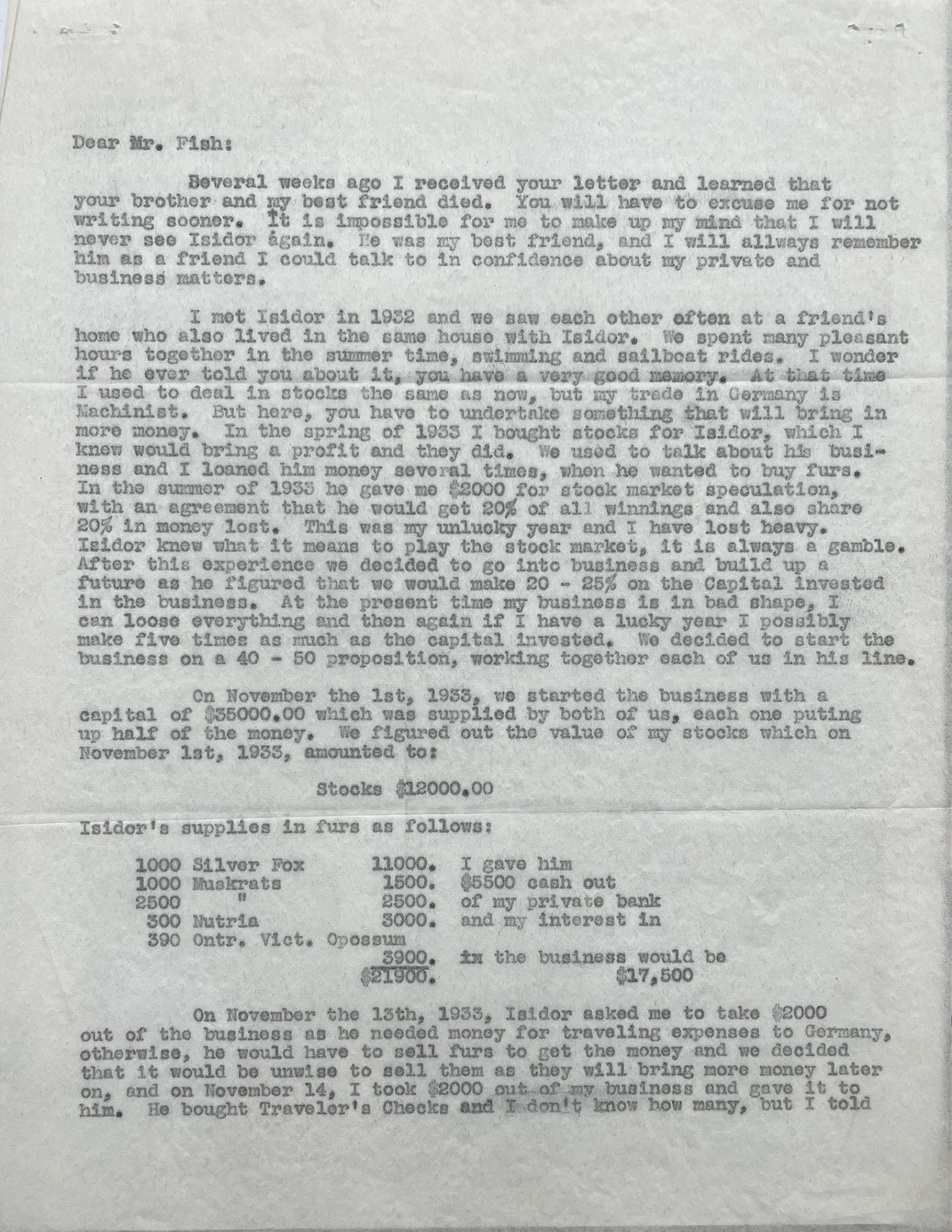

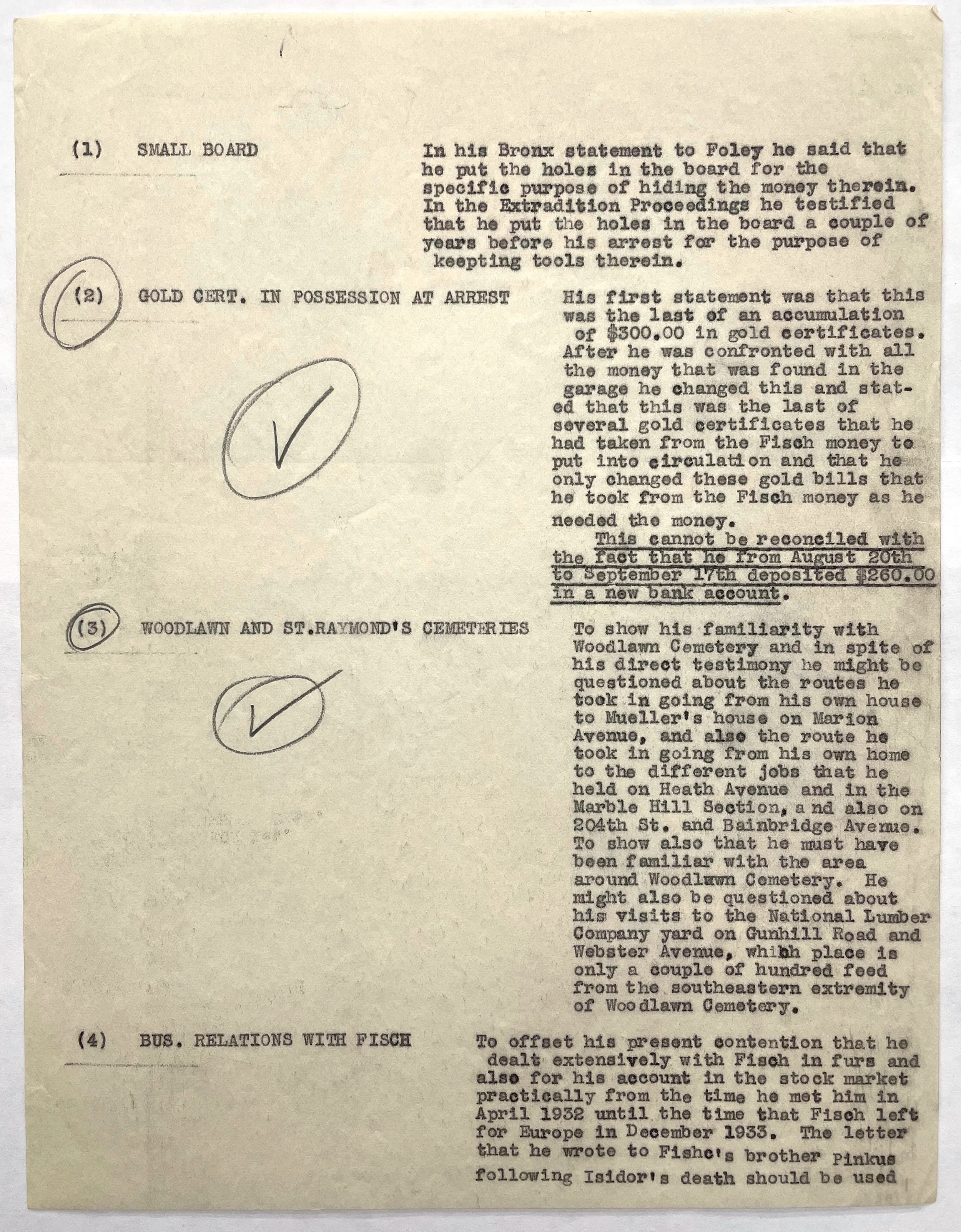

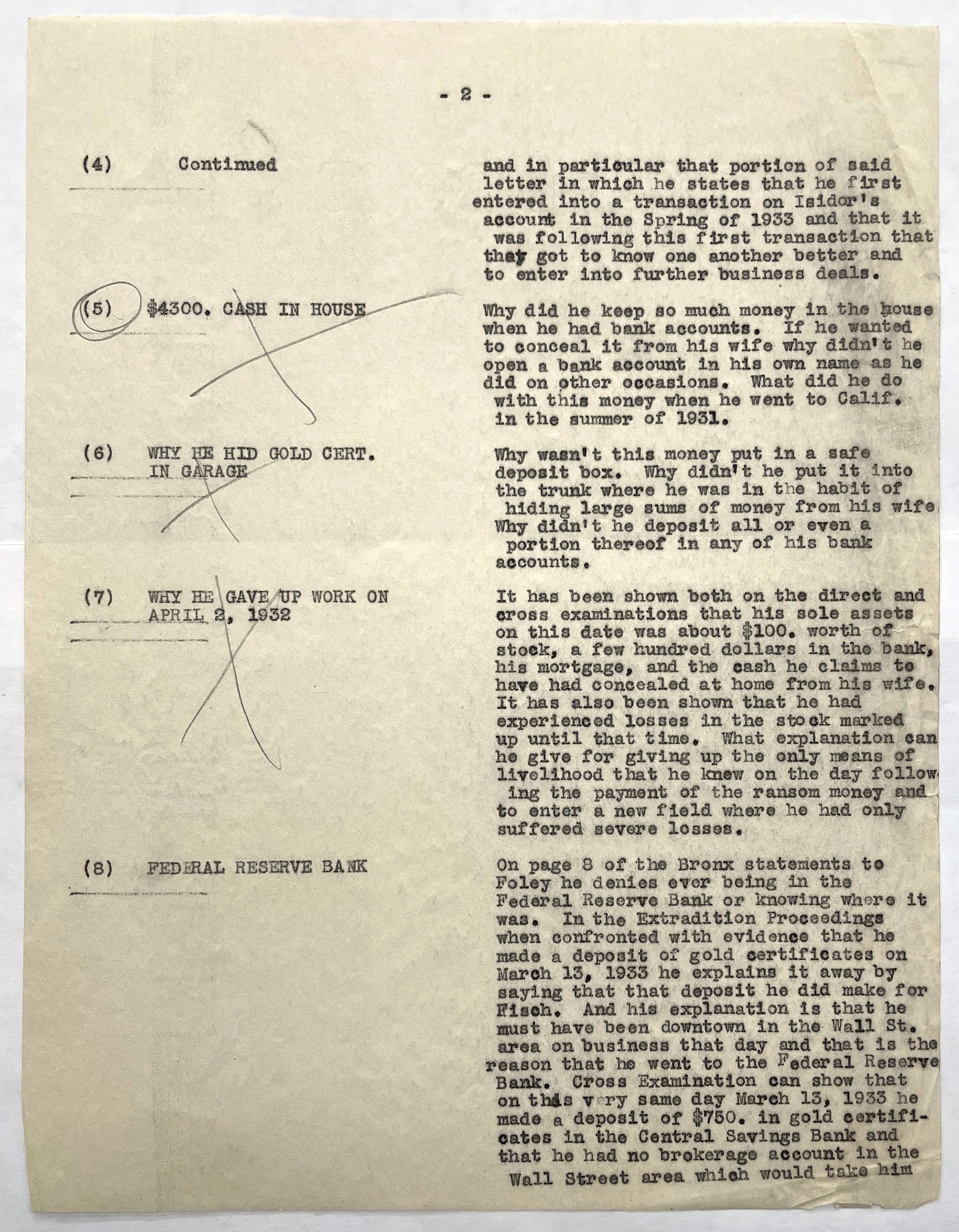

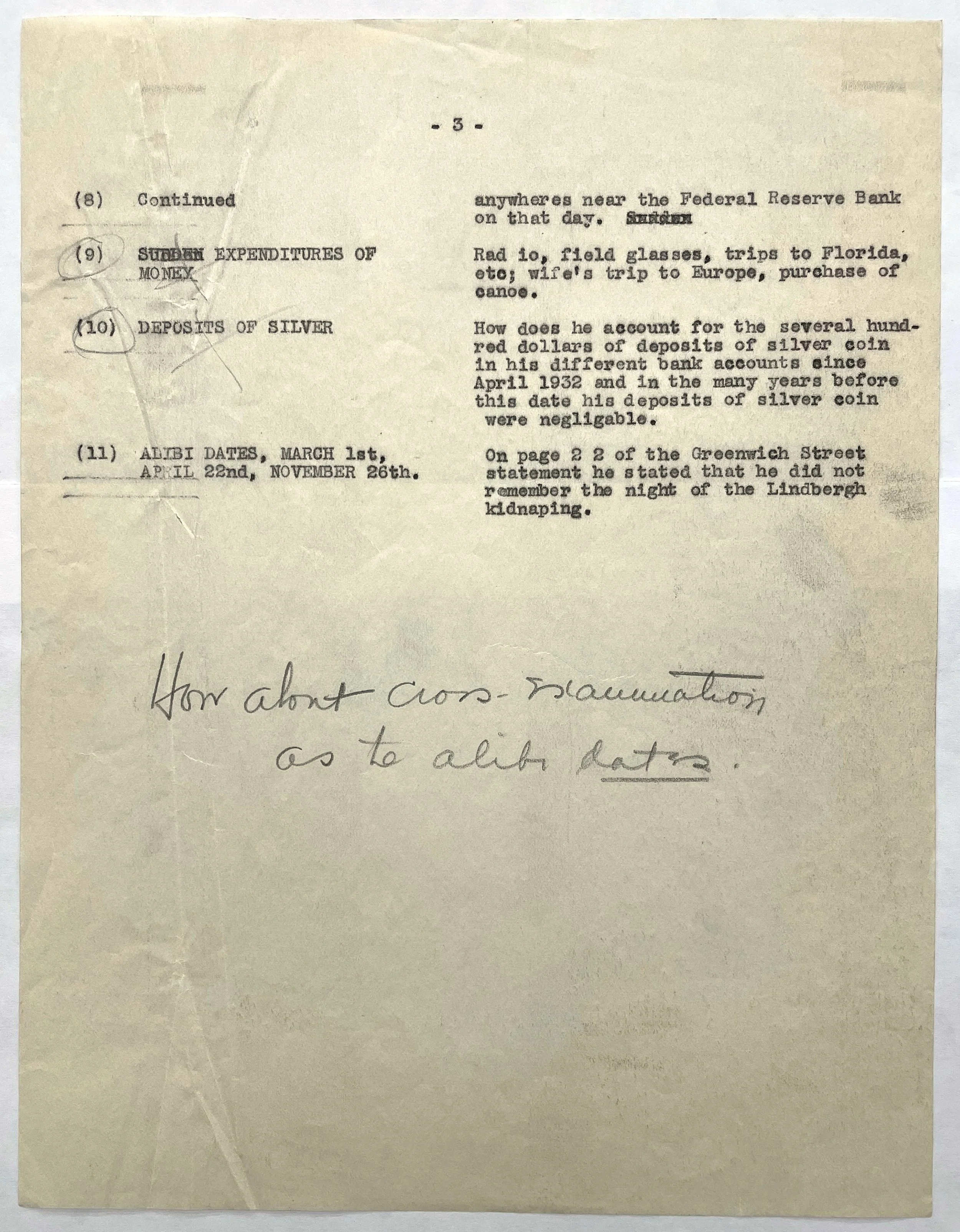

The Mayflower II sailing into New York Harbor, July 1, 1957. Department of Marine and Aviation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

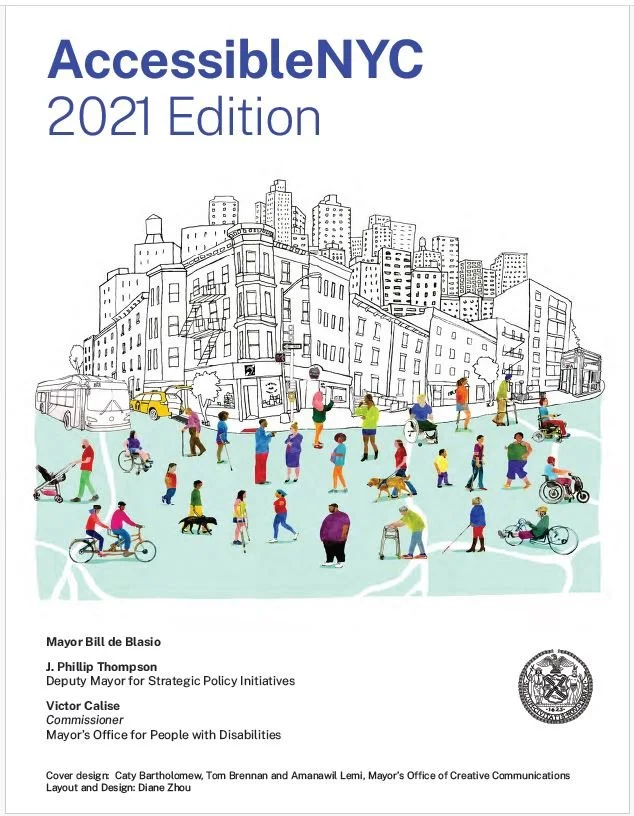

The sea voyage of the original ship Mayflower, in 1620, transporting religious dissenters, the “Pilgrims,” from England to New England has been a foundational legend in American history. The journey of the replica ship, Mayflower II, in 1957, is perhaps less well known.

The idea for the new ship developed on both sides of the Atlantic in the years following World War II. In England, a journalist and public relations man, Warwick Charlton, established Project Mayflower Ltd. in 1951. At the same time, officials at the Plimoth Plantation in Massachusetts (now known as Plimoth Patuxet) had a similar idea to research and design a ship the size and type of the original Mayflower. The two organizations eventually joined together to build the sailing vessel that became known as the Mayflower II.

The Mayflower II sailing into New York Harbor, July 1, 1957. Department of Marine and Aviation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

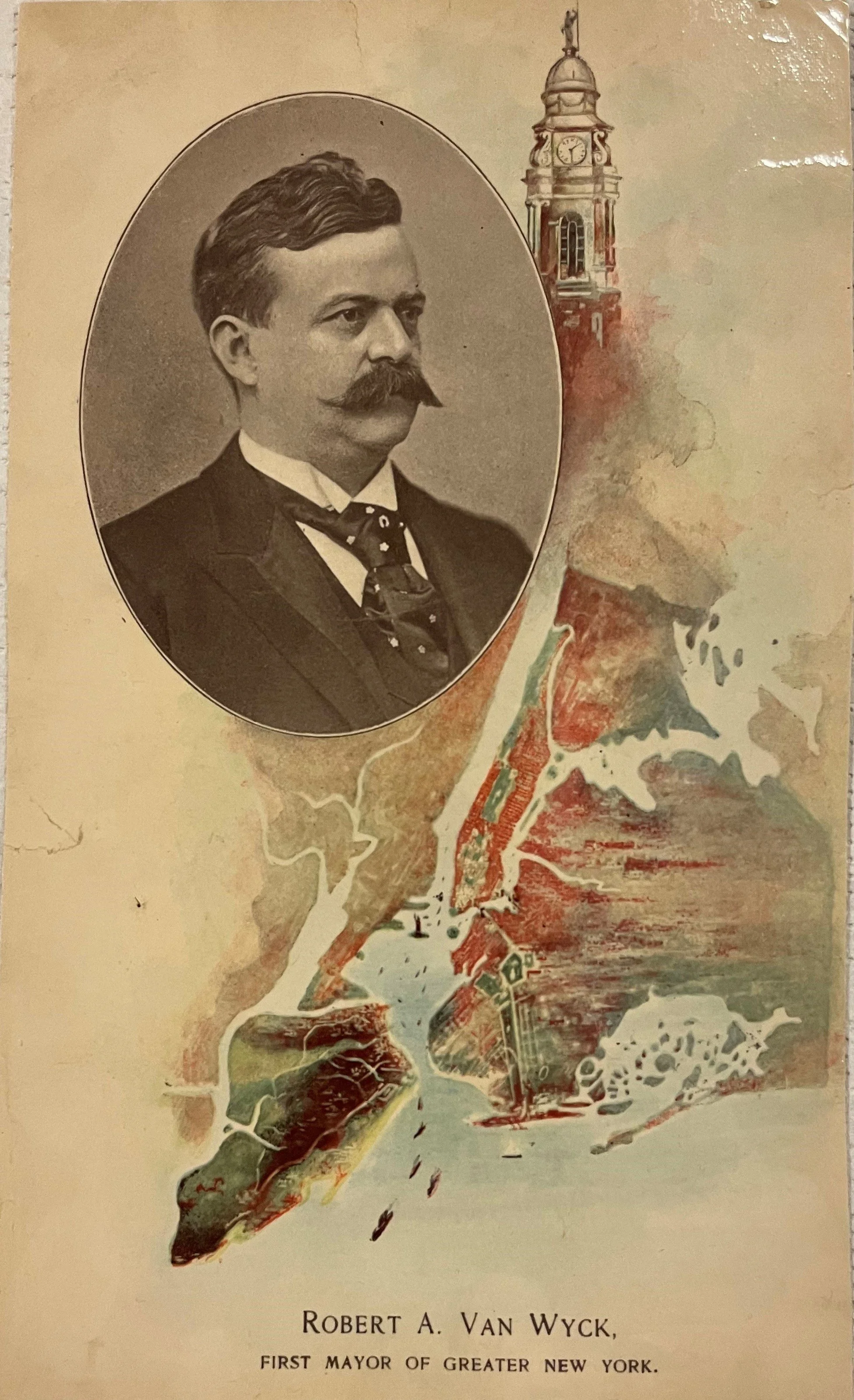

In 1956, when New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner learned of the project, he wrote Warwick Charlton and suggested that the new ship should make a stop in New York City before it berthed permanently at the Plimoth Plantation. “It is needless for me to remind you that there is no place in the world like the facilities of the seaport of New York City ... and in the summer receives millions of tourists and visitors.”

A carbon copy of Wagner’s letter can be found in the correspondence files of his Commerce and Public Events office. Grover Whelan, the City’s long-time official “Greeter,” had retired in 1953, but his work had been continued under the able leadership of Richard C. Patterson. Appointed by Mayor Wagner as Commissioner of the Department of Commerce and Public Events in 1954, “Ambassador” Patterson and his staff organized the festivities, including a ticker-tape parade, to welcome the Mayflower II and her crew.

On April 20, 1957, the Mayflower II set sail from Plymouth, England, bound for Massachusetts. Captain Alan J. Villiers, and his crew of thirty-three men, and one black and white cat, “Felix,” arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, on June 13, 1957.

Two weeks later, on July 2, 1957, the vessel sailed into New York Harbor. The front page of the New York Times the following day described the scene. “A salty-looking crew of adventurers received a cheering ticker-tape reception on lower Broadway at noon yesterday. They were the deeply tanned crew of the Mayflower II and, in their Pilgrim garb, they looked as if they might have just stepped off a Hollywood movie set.”

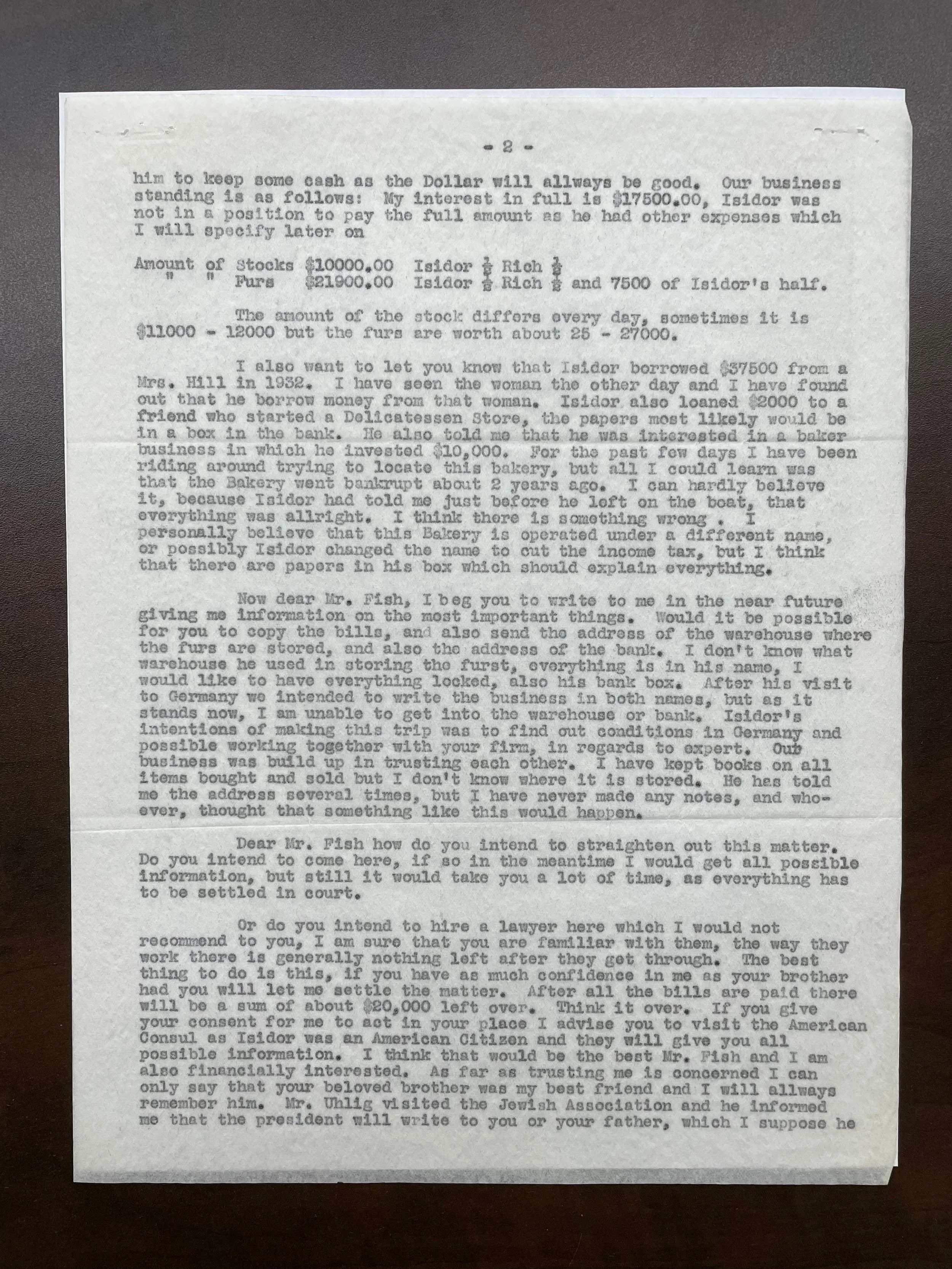

Costumed “native” Americans on the dock awaiting arrival of the Mayflower II, July 1, 1957. Department of Marine and Aviation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Times story failed to mention that not only did the Mayflower II crew dress in colonial-era garb, but a small troupe of young people, wearing “native” costumes greeted arrival of the vessel. The Times reporter also apparently missed the ceremonial presentation of a live turkey by the “native” group to ship’s Captain Villiers. The New York City Department of Marine and Aviation (DMA) photographer captured the scene. There is no documentation regarding the ultimate disposition of the gift-turkey.

Captain Alan J. Villiers, of the Mayflower II, wearing “Pilgrim” clothing, accepting gift of a live turkey from costumed “native” American, July 1, 1957. Department of Marine and Aviation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

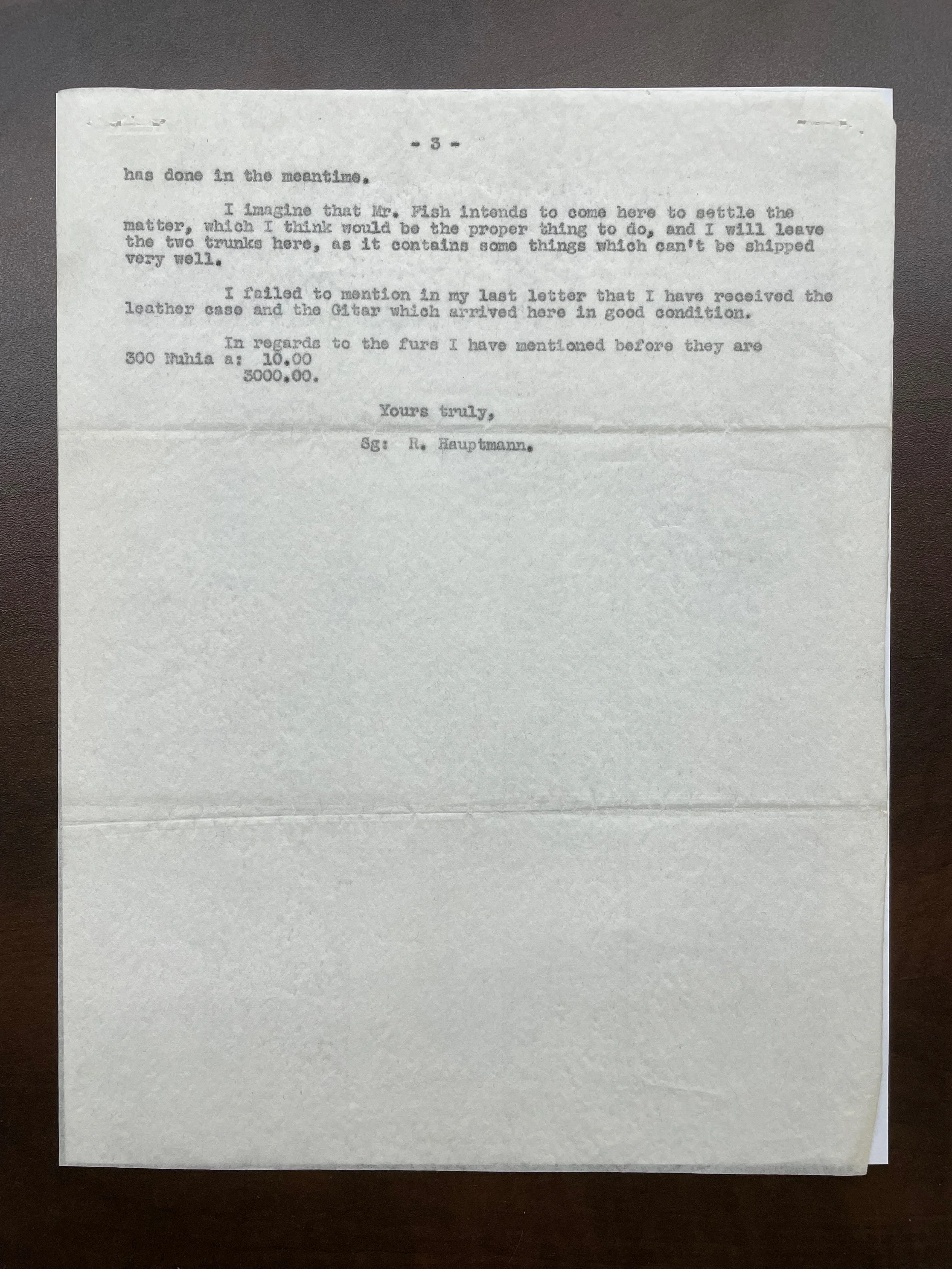

However, the Times did report on Mayor Wagner’s brief remarks on the steps of City Hall upon arrival of Captain Villiers and his crew after they paraded up Broadway from the Battery. “Of all the ships that have ever brought people to our shores, no one of them has meant more to America than the pilgrim ship Mayflower. For us, the Mayflower is at once the vehicle and the symbol of American freedom.” Wagner continued, “There were human beings aboard the first Mayflower . . . who were inspired by a dream of political and religious liberty.” And, he added, “In the centuries that followed, our nation’s destiny and greatness was shaped by millions of immigrants and refugees from oppression who displayed the same courage and determination.” The Public Events folder in the Wagner collection contains a complete transcript of the remarks, along with additional correspondence and event planning documents.

At the conclusion of the day’s ceremonies, the Mayflower II sailed up the Hudson River to Pier 81 at West Forty-first street. According to the Times, the Mayflower II and exhibits, “will be opened to the public today at 10:30 A.M. by Ethel Merman, the musical comedy star. Tickets will be sold for 95 cents for adults and 42 cents for children.”

Mayor Robert Wagner shakes hands with Mayflower II Captain Alan J. Villiers, City Hall, July 2, 1957. Crewman Andrew Anderson-Bell holds ship’s cat, “Felix,” the only feline known to have participated in a ticker-tape parade. Department of Marine and Aviation Photograph Collection, NYC Municipal Archives.

The Mayflower remained berthed at Pier 81 and open to the public until November 18, 1957. An estimated 500,000 visitors explored the vessel during its stay in New York City. Two weeks later, on Thanksgiving Day, November 27, the ship was officially turned over to Plimoth Plantation where it became part of a permanent restoration of the earliest Pilgrim settlement in America. More recently, after a three-year restoration, in October 2020, the Mayflower II once again welcomed visitors.